Joseph Cornell and The Poetics of Enclosure

One December evening in 1936, visitors to the Julien Levy Gallery in Manhattan watched a very strange film.

Running the projector was the film’s creator, a thirty-four-year old former textile salesman named Joseph Cornell. His film, Rose Hobart – a re-edit of East of Borneo and named after that movie’s leading lady – combined scenes from the jungle melodrama with stock footage and other shots from unidentified films. Cornell showed the film at ‘silent speed’ (slowed from 24 to 16 frames per second), projected it through a blue glass filter, and replaced any traces of the original soundtrack with samba music, played from a record he had bought at a flea market. Even today, watching Rose Hobart is like finding yourself in a weird dream, the kind you wake from clawing the nightstand for a pen and paper. In the past month I’ve probably watched it at least a dozen times.

The film opens with a crowd gazing at an eclipse (a scene that is not in East of Borneo), then immediately cuts to a tense encounter between the movie’s romantic leads and crackles to a blank screen. Three seconds later, it restarts in disconnected sequences showing Rose asleep; wandering through palm-filled rooms; standing on a balcony; being courted and menaced in a lavish palace, and in one bittersweet scene, confiding in a captive monkey. Cutaways to a candle flame, moonlit clouds, windswept palms – shots which usually signal plot points or segues – disengage these scenes even further, and our focus shrinks to Rose. The film’s pace and swaying accompaniment compel us to follow her, but as she reacts to characters and events we cannot see, her experiences appear more and more discrete, each enclosing the next like Chinese boxes. The more we look for narrative causality in Rose Hobart, the less we find any.

The film’s kitschy glamour and dream logic is recognisibly surrealistic, and based on his use of collage, photomontage, and found objects, Joseph Cornell is commonly known as a surrealist. Certainly by 1936 – when his work was included in ‘Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism’ at the Museum of Modern Art – he was recognised as such. But Cornell was not only ambivalent about calling himself an artist, he was reluctant to align himself with any movement, and unlike the surrealists, he wasn’t interested in challenging the present, holding a mirror up to society or provoking a visceral reaction. Instead, he was fascinated with finding connections between different times and places, and his signature technique – boxed assemblages – is unique in modern art. So much so, in fact, that if his works were plotted on a Venn diagram, it would lie where the Wunderkammers of the early Enlightenment meet Victorian science meets coin-operated entertainment.

But above all, the power of Cornell’s boxes lies in the range of associations they evoke. They seem to contain worlds, opening a window onto what lies between reality and memory, what we long for and what remains.

Cornell’s actual entrée to surrealism came in 1931: walking along Madison Avenue in pursuit of a particular photograph by Nadar, he went into a new gallery. He got to know the owner, Julien Levy, and after showing him a series of small collages, Levy added him to a group show he was planning.

In January 1932, ‘Surréalisme’ opened at the Levy Gallery, the second surrealist exhibition in the United States[1], and it included Cornell’s work alongside that of Max Ernst, Salvador Dalí, Pablo Picasso and Man Ray. Later that year, Levy gave him a small solo show in the gallery’s back room, which Cornell filled with collages and arrangements of objects under bell jars or in pillboxes. He made everything at the kitchen table of the house he shared with his mother and his younger brother, late at night, after they had gone to sleep.

Born in 1903 in Nyack, New York, Cornell was the eldest of four children and enjoyed a comfortable, middle-class childhood until the age of fourteen, when his travelling salesman father died, leaving massive debts. He was sent to school in Massachusetts but left the Phillips Academy without graduating. To support his family - two sisters, an emotionally demanding mother and a beloved brother (who was later incapacitated by cerebral palsy) - he took up work as a textile salesman, commuting every day to Manhattan.

The job required a huge amount of legwork, and as he made his way from client to client, Cornell visited second-hand bookshops, five-and-dimes, department stores and arcades. He added regular trips to museums, libraries, and the many contemporary art galleries popping up throughout midtown. An avid moviegoer, he also went to the theatre and became a passionate balletomane. He documented his various passions in scrapbooks containing notes and clippings from magazines, nineteenth-century prints, Victorian novels and old textbooks. He developed pages into collages and then experimented with pictorial and sculptural combinations to produce his first objects.

Cornell often made repeated revisions, which renders any strict chronology of his work difficult, if not irrelevant, but a few of his early works indicate how two of his key passions – theatre, especially ballet, and science – possibly guided his transition from collage to box construction.

Tilly Losch (made around 1935 and titled several years later) features a Victorian girl floating above the Alps, suspended by delicate strings, as if she were not only travelling aboard an unseen balloon, but actually suspended from it, like a gondola. In A Dressing Room for Gilles, Cornell suspended Pierrot by a single ribbon within a narrow, mirrored box surrounding Watteau’s clown with harlequin reflections. Then, in an untitled homage to Tamara Toumanova, he imagined the Russian ballerina as a deep sea explorer riding a nautilus shell, crowned with a spirula. And in one of the first Soap Bubble Sets (his longest running series) seashells appear on glass discs ‘bubbling’ from a clay pipe, like specimens under a microscope. His iterations of hot-air balloons, ballerinas, stars and seashells reflect key interests, but also a fascination with certain abstract and metaphysical concepts, such as enclosure, suspension, and transcendence.

Arguably, Cornell’s talent lay not in his hands (he never drew, painted or sculpted anything, per se), but in his eye and his grasp of the associative power of words and objects. He explored Manhattan and the outer boroughs like Atget in nineteenth-century Paris, his senses attuned to the ephemeral, looking for the small, overlooked or discarded details that seen in the right context describe the whole.

He wrote down his daily experiences in notes, diaries and letters. He collected photographs, postcards, maps and charts, advertisements, bits of typography, lines and articles cut from magazines and books, and countless objects gleaned from job lots, manufacturing surplus, warehouse clear-outs and rubbish bins.

What’s more, he catalogued everything, not according to any conventional hierarchy or taxonomy, but by type (‘watch parts’, or ‘cordials’ for the tiny glass goblets he used), or by correspondence to certain symbols or narratives (‘centre of the labyrinth’ or ‘childhood regained’). Late at night, at his kitchen table and later, his basement studio, he drew words, images and objects from this vast archive of unwanted stuff and arranged them in glazed wooden boxes.

Cornell’s signature device embodies the basic paradox between limit and imagination that is unique to his work and initially, like everything else, these boxes were found objects, such as old sample cases. But by the late 1930s he began to construct them himself and one of his more sophisticated cabinet boxes is Untitled (Pinturicchio Boy), which he worked on for the better part of a decade. In this box he placed a photostat of Bernardino Pinturicchio’s Portrait of a Boy between wings gridded by iterations of the same portrait, details from unrelated prints and books, and numbers. In the predella space he included watch springs and collaged ‘dice’ and he enclosed everything behind a latched door fitted with amber glass. Part of his Medici Slot Machine series, Pinturicchio Boy combines childhood nostalgia with renaissance gravitas, illustrating that all games are games of chance, and that because we remain, as Rilke wrote, ‘beginners in the world’[2] we never out-grow our need for toys to help us make sense of it.

Cornell’s literary tastes often fed directly into his work. He read everything from Rainer Maria Rilke, Simone Weil and Alain-Fournier to John Donne, Gérard de Nerval, Arthur Rimbaud and Emily Dickinson. He particularly loved the fairy tales of Charles Perrault and Hans Christian Andersen. As an adult, Anderson actually played with toy theatres, a fact Cornell may have known when, in 1942, he began a series of palace-themed boxes.

Partly inspired by his friendship with Tamara Toumanova (whom he’d seen dance the role of Aurora in The Sleeping Beauty), in Setting for a Fairy Tale, he transformed his usual display cabinet into a proscenium opening onto a tiny, coherent stage set. His magic castle is a photostat reproduction of a sixteenth century engraving, and behind its cut-out façade, a black backdrop throws a forest of painted twigs into sharp relief. He added to the illusion of depth by enclosing the castle within a shaped black frame painted onto the glass. Finally, bits of mirrored glass in the window frames draw us into the work only to wink back reflectively, making us accidental performers in an imagined drama.

Cornell made at least nine of these palace constructions, perhaps because he not only understood how fairy tales endure in adult psychology, but that their resonance is part of our shared experience and not, as some surrealists argued, a sort of secret knowledge. His use of coloured glass to cast a unified glow over disparate objects and particular fascination with Sleeping Beauty encourages us to look for dream logic and symbolism. We root through these works like an old shoebox pulled from under the bed, and as we do we time travel, looping between actual recollection and nostalgia. Cornell couldn’t have read The Uses of Enchantment, but these boxes illustrate one of Bruno Bettelheim’s key theories: fairy tales endure because they reflect our innate desire to become better people.

Essentially, Cornell’s boxes preserve specimens of an idealised past, a logical progression from his bell jar objects. But certain recurring architectural themes suggest he imagined them as more than vitrines. In 1933, inspired by a handful of stereoscopic slides, he wrote a kind of screenplay, Monsieur Phot, a collection of scenarios set in a hotel involving a fictional nineteenth-century photographer and his struggles to capture life in still images. Cornell never made the film, but a few years later, he made Object: Hotel Theatricals by the Grandson of Monsieur Phot Sunday Afternoon.

Detail: Object - Hotel Theatricals by the Grandson of Monsieur Phot Sunday Afternoon (1940) Yokohama Museum of Art

He divided the space into sixteen cells arranged in four rows, each cell framing a stereoscopic photograph of the same young man. Several cells contain one or more blue glass marbles, unfixed. He labelled each row with a different title: ‘Jacob Wrestling with the Angel’ or ‘Triumph of Galatea’, maybe marking separate sequences or actions, or just to poke fun at some of the poses. The overall impression is frames from a nickelodeon and Cornell’s combination of sequential imagery with pin-ball animation suggests the paradox of framing human vitality.

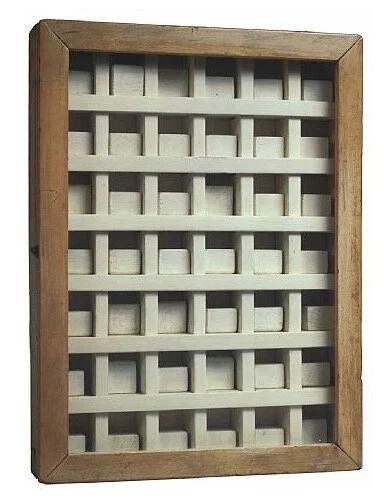

Around 1946, he began a new series encapsulating a particularly modern absurdity: serried solitude. The dovecotes - monochrome geometric arrangements in painted wood - suggest both traditional bird houses and high-rise apartment buildings and are arguably Cornell’s most austere works. But like the Medici Slot Machines and Setting for a Fairy Tale, the dovecotes invite viewer participation.

Standing before Untitled - Multiple Cubes, the work appears almost forbiddingly frontal. But subtle variations in the size, proportion and orientation of the cubes dramatically effects how we read it, because our perceptions shift with the merest movement. And by including moving objects in Dovecote - Colombier - unfixed wooden balls, both visible and partially hidden - he suggested hidden life behind the spare, grid-form composition.

Art historian Dawn Adès believed Cornell’s dovecotes were directly inspired by contemporary architecture, but also cited a 1950 diary entry referencing Jean-Thomas Thibault, whose treatise on perspective was well known in nineteenth-century academies. It’s worth noting that Cornell gleaned his remarkably detailed knowledge of European history, geography and culture almost entirely from outdated sources: old Baedekers, railway and shipping timetables, maps, postcards and hotel brochures. In fact he ‘knew’ Paris not as an actual city, but as a pastiche of fin-de-siècle experience.

Like Gérard de Nerval walking his pet lobster through the Palais-Royal – an image that would fit nicely in one of his boxes – Cornell wandered Paris as a basement flâneur, charting a path with nineteenth-century words and images. He made me think of Emma Bovary with her maps, obsessively tracing escape routes along streets she will never see. But while Cornell was deeply romantic, he was no solipsist, and if his tastes and imagination were rooted in the past, he was equally fascinated with the lives of those who had shaped that past. In fact, when he recounted anecdotes from biographies and memoirs, people often thought he was speaking of actual friends and contemporaries. When he first met Marcel Duchamp the two men discussed Paris in such detail that Duchamp was later stunned to learn Cornell had never been there.[3]

Grand Hôtel Sémiramis (1950)

Directly related to the dovecotes - at least thematically - are the various ‘hotels’ Cornell began to make from about 1945. It’s tempting to believe he knew of Thibault’s theatrical designs when he made Grand Hôtel Sémiramis, but any connection is probably more subtle because to Cornell, ‘hotel’ carried a double meaning: the popular appeal of foreign travel and the private grandeur of hôtels particuliers. Untitled (Hotel Eden), also features a parrot perched in a spare white space, and by 1945, caged vitality had become a recurring theme in his work, relating not only to his passion for birdwatching and the natural sciences in general, but also to his ardent pacifism. Throughout the 1940s he incorporated broken objects, fragmentary images and text, and refined techniques to enhance the ‘feel’ of these hotel boxes, distressing painted surfaces or baking them to create craquelure. Sarah Lea, curator of the recent retrospective at the Royal Academy noted that in the boxes Cornell made during and just after WWII, his focus on patina created ‘melancholic spaces of the past, faded glory, haunted by an absence made palpable.’[4]

The German sociologist Georg Simmel believed that no space better symbolised economic indifference to human welfare than the average hotel room. Like train stations and shopping arcades, hotels are a transitory space, defined only by the human activity erased from it daily. Cornell might not have read Simmel but, given his passion for astronomy, he probably knew Sir Arthur Eddington’s theories of stellar luminosity, and how the laws of physics operate irrespective of our understanding. He definitely subscribed to several popular science magazines and followed contemporary technology, such as the development of the Hale telescope and its use in discovering moons, stars, asteroids and the clouds of Neptune.[5]

Towards the Blue Peninsula - For Emily Dickinson (c. 1953)

The 1950s were an exceptionally energetic and confident time for Cornell as he developed his dovecote, aviary and hotel-themed boxes into ‘observatories’. In December 1949, he opened ‘Aviary’, his first solo show at the Charles Egan Gallery in New York, followed by two shows focusing on the theme of celestial navigation: ‘Night Songs and Other New Work’ (1950), and ‘Night Voyage’ (1953), which included Towards the Blue Peninsula (For Emily Dickinson), a box so empty that, as John Stezeker wrote, it ‘paradoxically achieve[d] … imaginary occupation’.

Even more minimalist is his homage to the pilot-inventor, Louis Blériot, where with only a watch spring, some doweling and a bit of blue stain, he evoked the Frenchman’s hand built biplane and the ocean waves it crossed. Around 1942, Cornell met Antoine de Saint-Exupéry during the two-year period he lived in the United States. The two men became friends, and Cornell’s dossier of notes, clippings and ephemera dedicated to Saint-Exupéry includes several sketches for the book, including one of The Little Prince himself, drawn on a cocktail napkin.

Cornell had read Saint-Exupéry’s memoir, Wind, Sand and Stars, where he described how flying for Aéropostale - via notoriously dangerous routes between North Africa and France - opened his eyes to the nature of friendship, solidarity and the meaning of life in a world that increasingly ignored humanity. He described the world as ‘a wandering planet’, limned by coasts and schisms, behind which nevertheless ‘lies something vaster … a path, a portal or a window opening on something other than itself.’

While Cornell’s own geography remained fixed, he shared Saint-Exupéry’s ageless curiosity and faith in the transcendental. What’s more, like the Little Prince, he never recognised hierarchies. He valued everything as being part of the warp and weft in a greater whole, and never developed a ‘grown-up’ sense of the generic. Stars could be celestial bodies mapping time and space or flesh-and-blood film stars, but neither definition had precedence. As the Little Prince tells the Pilot, stars are just tiny lights to most people; to travellers, they’re signposts, and to scholars, merely problems to solve: ‘but those stars are silent … You, though, you'll have stars like nobody else... since I'll be laughing on one of them, so for you it'll be as if all the stars are laughing.’

Cornell has been called a recluse or even an ‘outsider’ artist, but this is inaccurate or just flat-out wrong. Shy and self-taught, he neither married, nor aligned himself with any particular group. But he knew, befriended and exhibited with Abstract Expressionists, Minimalists and Pop Artists, and eventually he became a kind of lodestar for the American avant-garde. Most of the time he met friends, colleagues, curators and critics one-on-one at his home on Utopia Parkway in Queens. He befriended Duchamp, Pavel Tchelitchew, Dorothea Tanning, Lee Miller and Yayoi Kusama, made films with Stan Brakhage and Rudy Burckhardt, exhibited with Isamu Noguchi, shared his archives with Walter de Maria and Robert Whitman, and mentored Lawrence Jordan. He granted few interviews, but was invariably described as a gentle, generous, witty, intensely perceptive man with a weakness for cheap pastry and long Proustian digressions.

Filmmaker Ken Jacobs called Rose Hobart ‘a film as it was remembered’[6], and its subtle magic lies in how Cornell used pace, editing and the absence of diegetic sound to replicate the way we replay dreams. We’re initially drawn in by the original film’s exotic motifs, glamorous sets and costumes, and its beautiful leading lady, and Cornell’s focus encourages us to identify with Rose. But the key to the film’s strange resonance is his choice of found footage; how he arranged these seemingly unrelated scenes, and the dream logic they reveal.

The additional shots (i.e. none is in East of Borneo) are the opening crowd scene; a close up of a candle flame; light behind clouds (repeated and expanded); a splash with ripples (repeated and expanded); windswept palms (various); a chalice, and an eclipse. These shots bookend Cornell’s film, and interspersed with Rose’s reactions and encounters, build a second world around her.

We’re not drawn into Rose Hobart; we’re dropped right into it, and throughout the film Cornell directs our point of view and imagination. When we first see Rose she is reacting nervously to the Prince, but with no sound or dialogue, we have no idea why. A rough fade out distils this tension, sparking both prurient curiosity and concern for her predicament. The following tracking shot finds Rose asleep in a jungle camp. A candle burns. She awakens and emerges from the mosquito nets. A ball of light glows in the night sky. Then we see Rose again with the Prince, looking into the distance as she wrings her hands, but the scene cuts away to find her alone, walking through a palm-filled room. Something draws her to the balcony; she looks down. Cut to a shot of something unseen falling into a pool. The slow-motion splash and ripples elide the scene, making it unclear whether it’s something she actually sees, or merely remembers. She shakes her head, as if telling herself not to imagine things, but her smile fades as she raises her head and looks into the distance.

Scene follows scene, connected only by Rose’s gamut of emotions as she wanders through the same rooms, emerging discontinuously in strands of the preposterous original plot. One of Cornell’s more surrealistic additions interrupts a seduction scene: a close-up of a full chalice with a small cup bobbing on the surface. The cup appears filled with something white and not quite solid, which, as it sinks, reveals itself to be a sieve full of cotton wool.

For nearly twenty minutes, we follow Rose, transfixed by the film’s artificially slowed pace and constant tonal shifts. Shots of windswept palms - a relief from East of Borneo’s ornate sets and frequent night scenes - redirect our attention to the sky. As the film progresses, the edits become more abrupt, flickering between Rose’s reactions and those of the other characters before cutting away once again to the glow in the night sky: the lunar eclipse. As the eclipse peaks and wanes, the film ends with a repeat of the pond-splash, now expanded to include the fallen object, and slightly sped up to dissipate the ripples, smoothing the pond’s surface to reflect the moon.

Initially, Rose Hobart met with mixed reviews, except for one unequivocal reaction from Salvador Dalí, who screamed at Cornell calling him a thief, ranting that he had stolen the film from Dalí’s dreams. Then he tried to kick over the projector.

Cornell never employed direct symbolism. If objects, words and forms meant anything beyond themselves, it depended upon layered, highly subjective associations, in other words, dream logic. But if he actively looked to dreams for inspiration, it was because he recognised them as a common language. As Michael Pigott noted: ‘If the Surrealists hoped to use dreams as a means to disrupt the everyday, then … Cornell harboured a utopian desire to use dreamtime as a starting point for a re-appraisal of the everyday.’[7]

Rose Hobart is a delightfully strange film not because of any specific story it tells, but because it completely rejects narrative. At first, we see Rose through a lens of retro glamour and melodrama, but we end up identifying with her because Cornell’s editing encourages us to see things through her eyes. So, as we watch, we find ourselves like Rose, framed inside events that go seem to go nowhere, but might, if read individually, reveal some meaning.

Cornell’s Rose exists not only outside of any story but outside of time. I think he understood that we seldom plot precise moments in our own experiences. When we recall events that shaped us, we do so through our senses, through memories triggered by the material world, one we furnish, each, according to our own detritus.

Like his signature boxes, Cornell’s Rose Hobart draws us into a world recalled from another time, another life, or maybe just from a really great dream. It’s an oddly comforting film.

NB, My title is taken with gratitude from Jennie-Rebecca Falcetta’s essay comparing Cornell’s work with the poetry of Marianne Moore. I simply could not come up with a better title, believe me, I tried. (See Falcetta, Jennie-Rebecca. “Acts of Containment: Marianne Moore, Joseph Cornell, and the Poetics of Enclosure.” Journal of Modern Literature, vol. 29, no. 4, 2006, pp. 124–144. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3831883. Accessed 8 April 2020.)

[1] In 1931 the first surrealist exhibition in the US took place in the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Connecticut.

[2] https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2018/05/25/the-unfortunate-fate-of-childhood-dolls/

[3] Jasper Sharp, ‘The Pierrot Who Never Saw Paris: Joseph Cornell and His Relationship with Europe’, in Joseph Cornell - Wanderlust, exhib. cat. (London: Royal Academy of Art) 2015, p. 52.

[4] Sarah Lea, Royal Academy, op. cit., no. 57, p. 193.

[5] Peter Conrad made this particular connection between Simmel’s and Eddington’s respective theories in his essay ‘The End of the World in Berlin’ in Modern Times, Modern Places: Life & Art in the 20th Century (London: Thames & Hudson) 1999, pp. 322-323.

[6] Pigott, M. (2013). Notes. In Joseph Cornell Versus Cinema (pp. 113–118). London: Bloomsbury Academic. Retrieved April 3, 2020, from http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781472544728.0008

[7] Pigott, M., op. cit., p. 83.